Last week Eric Yuan, CEO of the now exhaustingly ever-present video conference company Zoom, told investors that Zoom would not offer encryption services to free users. Why? Because of Zoom’s commitment to supporting and aiding the FBI and local police officers.

As social distancing requires unprecedented reliance on the internet, and the ongoing Black Lives Matter protests bring people’s attention to the importance of digital security, Zoom’s decision is a reminder that technology is never neutral.

Last week Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, a digital artist, posed a simple but fundamental question in regard to the unfolding political movement: “How can I be useful as an artist?” Many contemporary artists are critically engaging with technology to answer that question. Here are five artist-made tools that support protests on the ground, resist surveillance’s biased gaze, fight back against social alienation and combat technologies imbued with anti-Blackness.

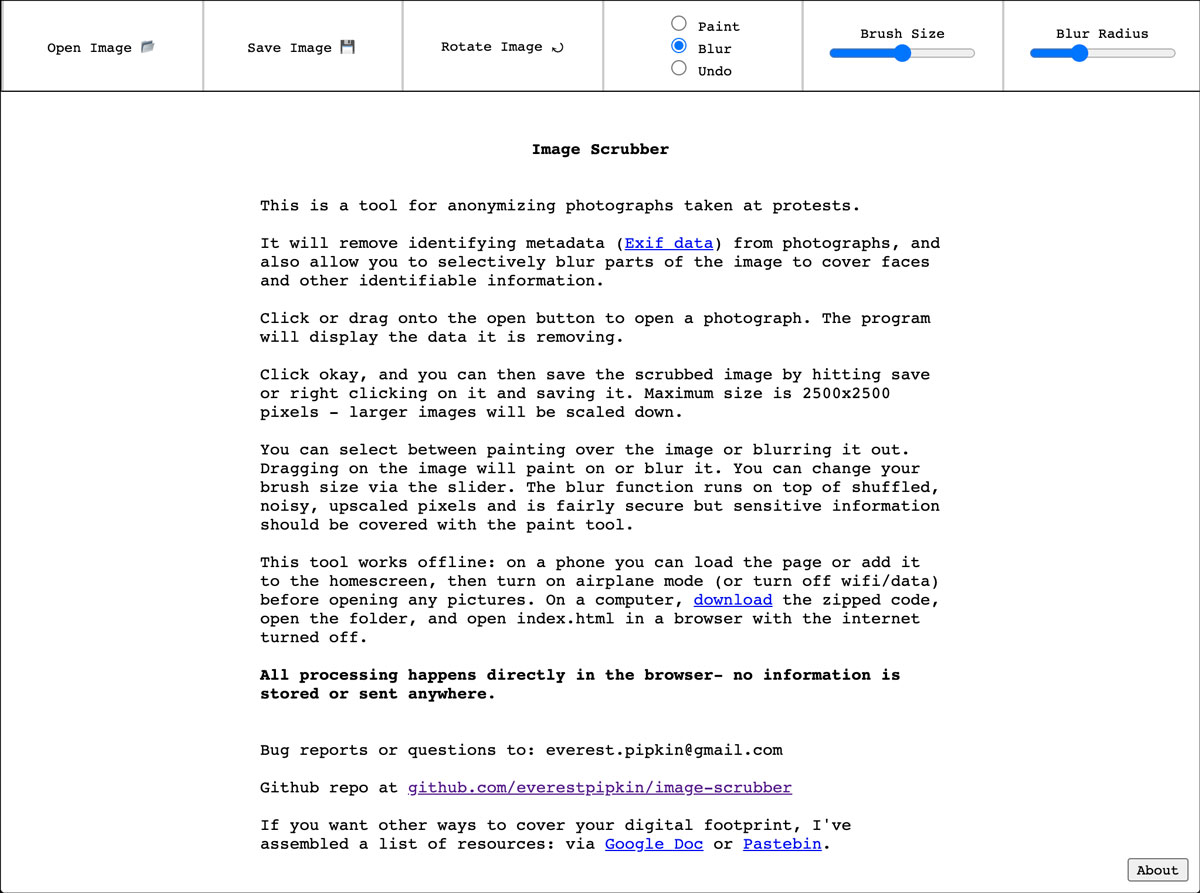

Image Scrubber

Artist Everest Pipkin’s Image Scrubber removes metadata from digital photographs and allows users to selectively blur faces and other identifiable features. With so much concern over images of protests potentially being used to make arrests, this tool protects the identities of those fighting for change, while still leaving space for the documentation of their actions.

While many of the artist’s other projects are more poetic in nature, Pipkin designated this particular technology as a tool, not as a piece of art. This decision is reflected in Image Scrubber’s practicality: it works offline, can be accessed on a phone, and does not save or store any user information.

Autonets

To empower communities that regularly face systemic violence, micha cárdenas, an artist, poet and professor at UCSC, designed wearable mesh-networked electronic clothing, which she calls Autonets, that radiate private communication servers. When groups of people wear these pieces of electronic fashion they join ad-hoc autonomous communities, within which they can set their own communication codes and conducts.

cárdenas imagines myriad ways this technology could be useful. She envisions it as a possible tool for sex workers organizing to protect each other, a mechanism for information to be dispersed at protests, or a way for communities of color to come to each other’s aid in the event of police harassment. It’s a digital tool that empowers people to make collective decision-making to combat not just emergencies, but a larger sense of alienation caused by forces like capitalism, white supremacy and neo-colonialism.

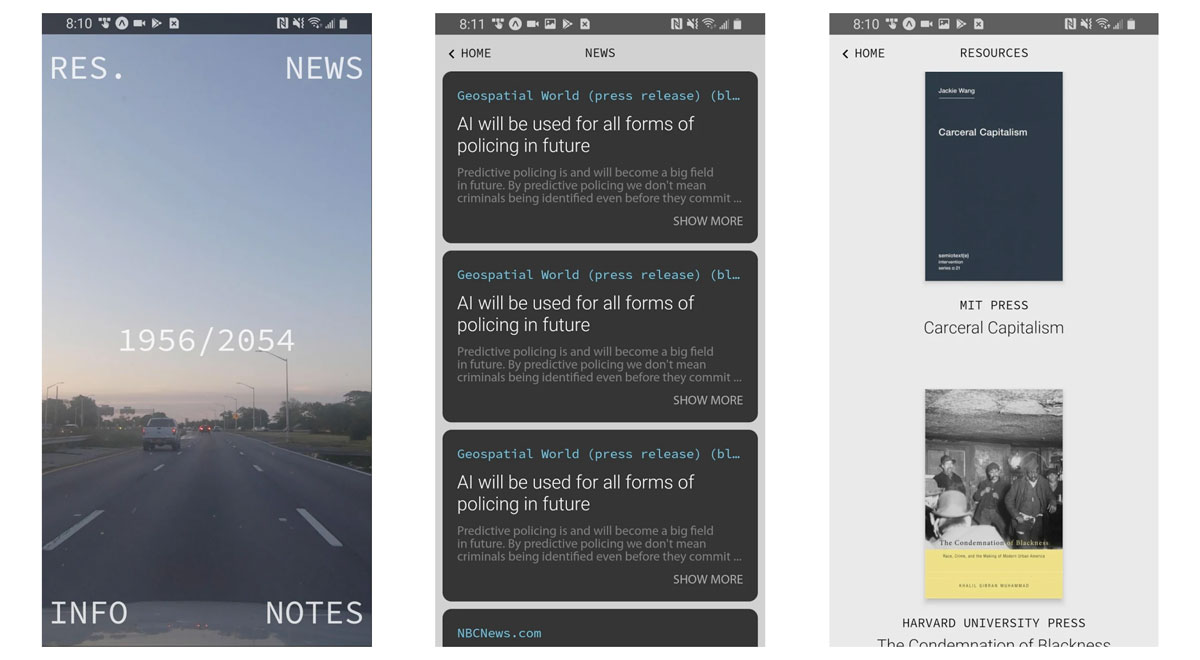

‘1956/2056’

In a recent interview, American Artist, the artist, writer and publisher who changed their name to become unsearchable on the web, said, “I think the best way to understand how high technology is anti-Black is to consider how the United States is anti-Black.” Their work interrogates the way technology racializes visibility and uses predictive algorithms to police the future.

As a part of their 2019 Queens Museum exhibition My Blue Window, American Artist built 1956/2056, an app that imagines the visual experience of an AI tool which dispatches officers to areas deemed high-risk crime zones. No crimes ever appear in their footage, the resulting video is almost banal. In this critique of predictive policing, the imagined future of Black criminality is not realized. The app also allows users to take notes and receive notifications about new articles on predictive policing, doubling as a community resource.

‘Oversight Machines’

For the past six years, artist and UCSC PhD candidate Abram Stern has focused on alternatively visualizing censorship in surveillance footage made public by the government. In one version of this series, which he calls Oversight Machines, he worked with FBI aerial surveillance footage of the 2015 Baltimore uprising to remove the video’s pixels and leave only information produced by the infrared and LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) sensors; Stern says this “conceals the surveilled while retaining the apparatus of surveillance” and replaces absence with a form of transparency “rich in politics, in aesthetics, in poetics.”

To illustrate the transformed surveillance footage’s poetic and political potential, Stern has collaborated with UC Davis professor and performing artist Margaret Laurena Kemp to overlay media generated by the Oversight Machine over video documentation of Kemp’s five-hour durational performance, Surveillance Like a Hollywood Movie, which incorporates movements from African American vernacular dance and manual labor. Their collaboration, Stern writes, “explicitly makes visible a racialized body who consciously meets the surveillant gaze.”

Future Technologies

In an interview, Dorothy R. Santos, Filipina American writer, artist and educator who co-founded the collaborative and politically engaged arts platform REFRESH, and is the program manager of the Processing Foundation, shed light on many of the artists included in this piece. In addition, she emphasized the importance of thinking about the technologies that don’t yet exist.

“When people think of political tools,” she says, “they too often go straight to protest. I want to also think about tools for healing, and tools that aren’t being created because it’s assumed that they aren’t needed. The grief in the air right now, it won’t just dissipate. Where are the technologies that enable a process of care?”

After protest, there is care work. After action, there is reflection and mediation. As we move into this next phase of action and change, it’s important to support artists, specifically Black artists, indigenous artists and artists of color, working with technology. Questioning just who is making the digital tools of our future is necessary—not just now, during a time of national focus, but always.