Queer Convoys: American Imperial Militarism and Global Asian Cultural Production

“’Terror’ talk is the new race talk—the ‘terrorist’ (or the ‘militant’ or the ‘radical’) is the twenty-first century way of saying ‘savage.’” –Sohail Daulatzai and Junaid Rana, “Left”

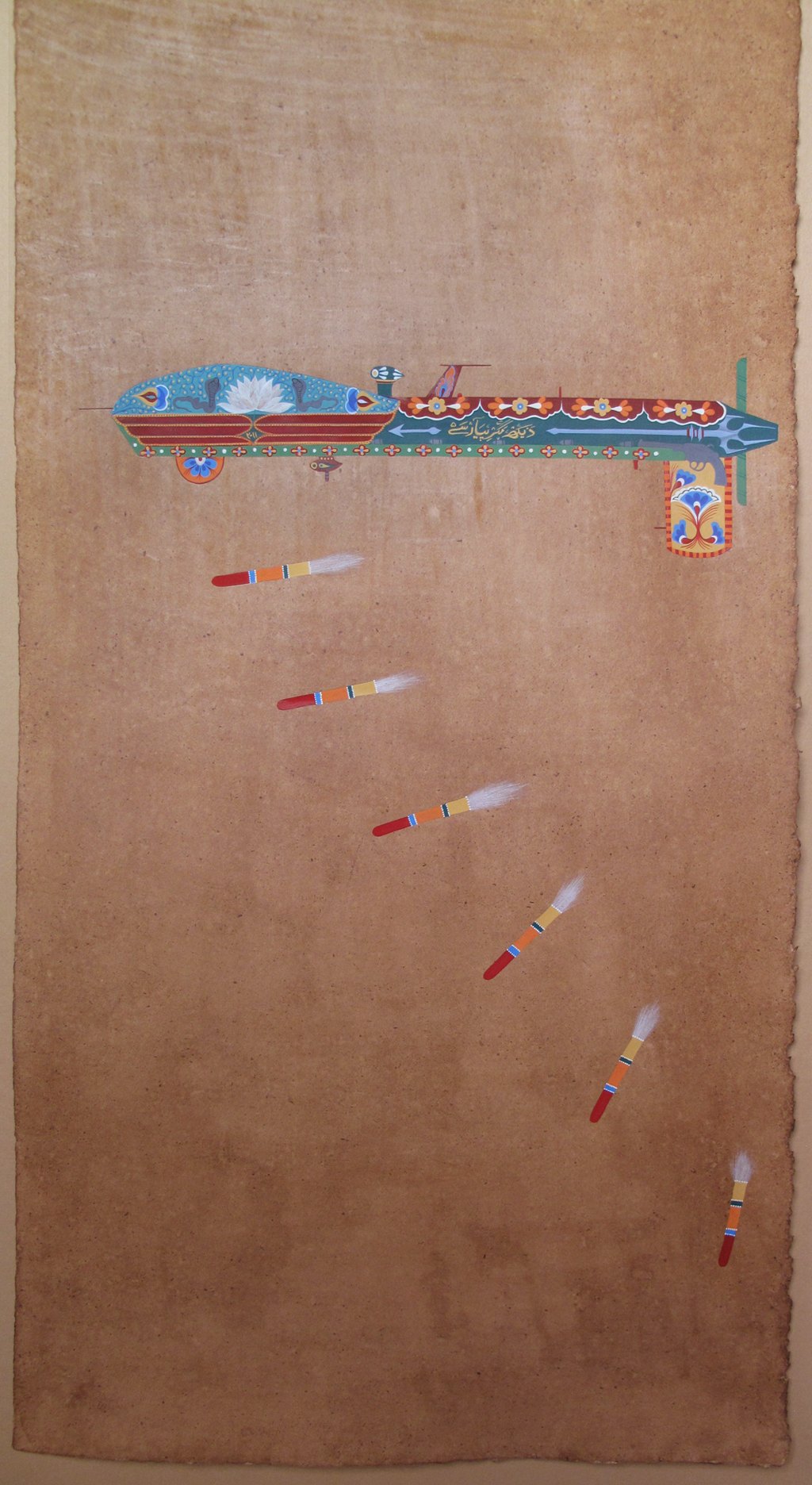

A maddening amount of technological and socio-cultural shifts have cast the twenty-first century in the markings of warfare in perpetuity. The aircraft is the physical leitmotif of contemporary American empire, a form that implies stealth and secrecy; an omniscient, asymmetric, and aerial gaze, through which it deploys violence from the sky. For some theorists and cultural practitioners responding to contemporary militarism (e.g. artist Mahwish Chishty; work pictured below), the drone has become emblematic of American imperial warfare, cloaking the chaos of panoptic surveillance in the language of “precision” at the expense of human life(1)

From artist Mahwish Chishty’s "Drone Art" (2011) series; uses Pakistani folk art aesthetics—borrowing from the tradition of truck art—to recontextualize the drone. Materials: gouache and tea stain on paper.

Investigating American imperial militarism in its ongoing forms requires a decidedly interdisciplinary framework. To understand its idioms, its ubiquitous underlying logic, and its manifestations of new aesthetic and cultural practices have been adopted. Therefore, my research draws on critical race theory, literary theory, and queer theory, and lies at the nexus of Asian American studies and postcolonial studies. Several key cultural responses to American imperial warfare—cultural artifacts being widely construed here as residing in image, text, sound—compel a rich analytic to critically engage with the aesthetics of contemporary war. I uncover a unique archive tracing American imperialism in Asia, and then choreograph the movement of this archive to show how previous American imperialist endeavors abroad come home to haunt the events leading up to and under the War on Terror.

My work is invested in the search for a queer politics in the age of permanent war, a politics that dissents the normativizing logic of American-led imperial warfare. My research is littered with many questions varied in scope. Those central urge us to develop a politics around aesthetic, literary, visual, aural, historic, and popular endeavors. How can we identify sources of dissenting cultural production in an age of homonationalism and permanent war? What forms do cultural responses take and how do they imagine, locate, and distill imperial power, as deployed by American militarism under the so-called War on Terror? How can a queer politics help to stake out claims of subjecthood for targets that are racialized, queered, and dehumanized and imbricated by U.S. power as objects of war terrain?

photo of Talib sitting in a historic mosque/mausoleum called Bibi Pak Daman.

By reading queerly American stealth and asymmetric warfare, I search for potential recourse against the displacement and the disembodying violence enacted onto the targets of war. Gayatri Gopinath (2005) theorizes the potentiality in queer diasporas for refiguring the concept of home in both national and diasporic terms; queer diasporas, she argues, suggest alternative forms of collectivity and communal belonging(2). I suggest that queer theory furnishes an analytic that subverts the binaristic logic of war implicit in the construction of at home versus abroad, “with us” or “against us,” “axis of evil,” and “coalition of the willing.”

In this vain, San Francisco-based artist Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s drag persona, Faluda Islam, challenges the normative logic of the global War on Terror. A zombified oracle resurrected through wireless technology, Faluda Islam embodies queer temporalities and collapses the queer and the racialized Muslim—at once sexually liberated, deviant, and a threat to homeland security—into one high femme body as a force for queer revolution, an embodied battleground against homonationalist and imperialist militarism.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s drag persona, Faluda Islam.

(1)See, for example, Drone Theory (2015) by Grégoire Chamayou, artist James Bridle’s “Drone Shadows” (2012-2014) series, and Mahwish Chishty’s “Drone Art” (2011) series.

(2) Gopinath, Gayatri. Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures. Duke Univesrity Presss, 2005.