Coming of Age in South Central: Gender Ideologies, Youth Activism, and The Carceral State

On September 15th, I joined Black and Brown youth activists at the Los Angeles Unified School District headquarters as they rallied to continue their calls to defund the second largest school police department in the country. Earlier that summer, LAUSD voted 4 to 3 to defund the Los Angeles School Police Department (LASPD) by $25 million. I took the picture above that September 15th evening after adult allies formed a protective barrier to prevent counter protestors from reaching the youth-led rally. As I wrote in October:

About 20 minutes into the rally, 35 or so counter-protesters, many of whom were off-duty officers, arrived accompanied by the lyrics of Toy Story’s “You’ve Got a Friend in Me.” The song blasted out of the motorcycle of a counter-protester who revved his engine in sync with “Black Lives Matter” chants in an attempt to drown them out. The counter protesters arrived as libations were being poured in memory of Breonna Taylor, Andres Guardado, Dijon Kizzee, and the countless others murdered by the police. Some of their signs read “Keep Our Kids Safe,” “Protect Our Kids,” and “Defend School Police.” While drawn in different colors, fonts, and material, what connected all the signs was the exclusion of Black youth from notions of safety and protection. [1]

During my time at UCSC, I have been researching how carceral logics (like that of the counter-protestors), carceral violence, community-based youth organizations, and social movements shape (and are, in turn, shaped by) the lives of inner city Black and Brown young men in Los Angeles County. Either as direct targets or witnesses of systemic racism, surveillance, exclusionary immigration policies, and police violence in their communities, youth of color pay the price of our investments in carceral logics. Youth of color, however, are also actively participating in and witnessing nationwide efforts to protect low-income communities of color from carceral violence. Within the context of these vibrant youth movements, I examine (1) how carceral violence shapes the social world of Black and Brown young men in an inner city context; (2) how neighborhood organizations like youth-servings groups, and their organizational practices, mediate and buffer carceral violence; and (3) under what conditions Black and Brown young men activists draw on intersectionality to develop a collective action frame in their efforts to decriminalize youth of color.

I ground my work in theories of intersectionality and Black feminist theory more broadly, youth studies, critical race theory, and critical carceral studies, to examine political mobilization by Black and Brown youth, gender ideologies, carceral logics, and youth-well-being. For example, in a manuscript currently under-review, Andrea Del Carmen Vazquez (CRES DE in the Department of Education) and I draw on antiblackness as a theoretical framework to situate school boards as racialized organizations that depend on antiblackness to animate a universal carceral apparatus. [2] Drawing on two case studies in California—one in an urban city and the other in an agricultural community—we demonstrate how racialized organizations utilize ideas of “safety” and “protection” throughout different education landscapes to fuel the perpetuity of anti-Black carceral logics.

As calls to reform or abolish the carceral state are situated as critical to the health and well-being of youth, my research reveals the individual, policy, and systemic meanings, consequences, and implications of carceral violence and carceral logics. Most importantly, I highlight the robust intersectional and abolitionist critiques, practices, and movements Black and Brown youth are developing. At a time when the carceral state is taking life and preventing it from happening, it is in those critiques, practices, and movements, where I see abolitionist futures begin.

You can read more about my work and publications at urielserrano.com

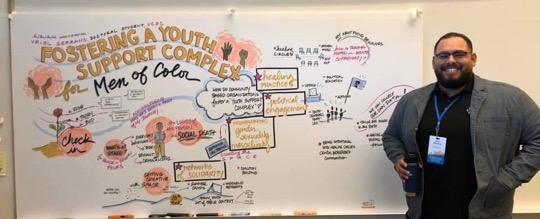

“Fostering a Youth Support Complex.” Photo taken by Eligio Martinez

[1] “Lessons Learned From the Los Angeles Youth Movement Against The Carceral State” in The Latinx Project’s Intervenxions. Special Issue on Latinx Politics — Resistance, Disruption & Power. Available at: https://www.latinxproject.nyu.edu/intervenxions/lessons-learned-from-the-los-angeles-youth-movement-against-the-carceral-state

[2] Hartman, S. V. (1997). Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. Oxford University Press; Ray, V. (2019). A theory of racialized organizations. American Sociological Review, 84(1), 26-53; Sharpe, C. (2016). In the wake: On blackness and being. Duke University Press’ Shange, S. (2019). Progressive Dystopia: Abolition, Antiblackness, and Schooling in San Francisco. Duke University Press; Shedd, C. (2015). Unequal city: Race, schools, and perceptions of injustice. Russell Sage Foundation; Spillers, H. J. (1987). Mama's baby, papa's maybe: An American grammar book. Diacritics, 17(2), 65-81.