Images of the Vietnamese Human: Visuality and the U.S. War in Southeast Asia

Most college students in the U.S. are exposed to the visual archive of war in Southeast Asia from 1964 to 1973 through news footage used in documentaries, fictional

Yet decades before formal U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia, very different kinds of images introduced Vietnamese subjects to American spectators with similar effects. In the late 1940s, Life magazine published a photo essay on the former French colony

Americans watching the Tet Offensive on television. Warren K. Leffler. 1968.

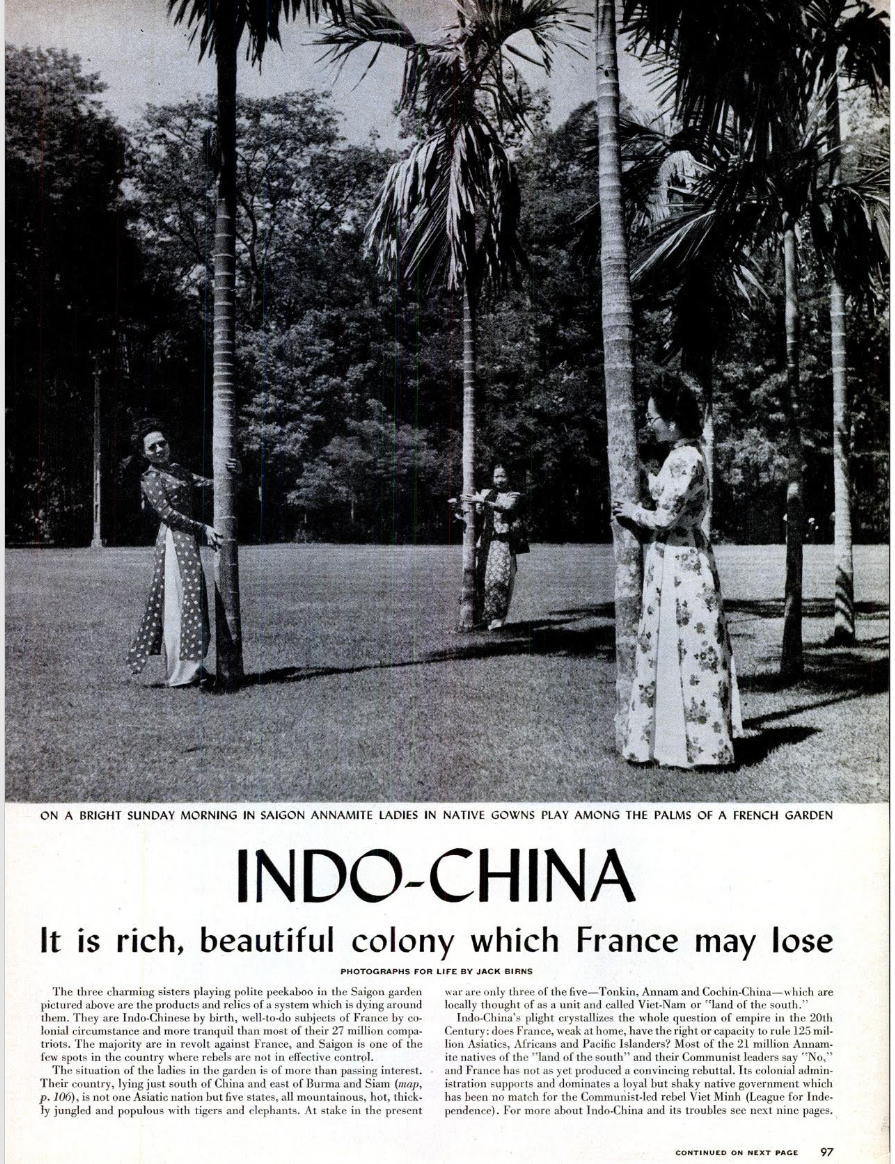

The cover photo depicts these imagined narratives clearly: three “Annamite” women (“Annam” was the name of the French colony of central Vietnam until 1948), in luxurious ethnic-modern clothing, leisure freely in a beautifully manicured garden. Unlike the images of brutality in the following decade, this image sought to generate feelings of similarity and civility between the Vietnamese subjects and the Americans who viewed them. Yet like the images of humanitarian

These photographs were used to expand the reach of America’s burgeoning empire across the Pacific and consolidate the national body in a moment when anti-racist movements exposed the fundamental violence of the nation-state. Similar photos would be published about Malaysia, Burma, the Philippines, and China. This history ought to move us to think carefully about the narratives imbued in images to consider what they tell (and don’t tell) us about the dynamics of power in an age of mass media, permanent war, and racialized violence.

“Indo-China”, Page 97, Life, March 7, 1949.